by Glenn R. Swift

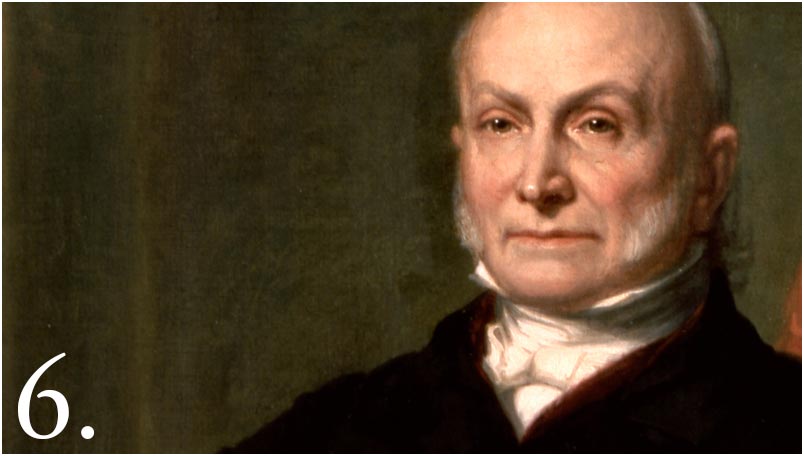

John Quincy Adams, son of John and Abigail Adams, served as the sixth President of the United States from 1825 to 1829. A member of multiple political parties over the years, he also served as a diplomat, US Senator, and member of the US House of Representatives.

The first President who was the son of a President, John Quincy Adams in many respects paralleled the career as well as the temperment and viewpoints of his illustrious father. Born in Braintree, Massachusetts in 1767, he watched the Battle of Bunker Hill from the top of Penn’s Hill above the family farm. As secretary to his father in Europe, he became an accomplished linguist and assiduous diarist.

After graduating from Harvard College at age 20, Adams became a lawyer. At age 26, he was appointed Minister to the Netherlands, then promoted to the Berlin Legation. In 1802, he was elected to the United States Senate. Six years later, President Madison appointed him Minister to Russia.

Serving under President Monroe, Adams was one of America’s great Secretaries of State, arranging with England for the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, obtaining from Spain the cession of Florida, and formulating with the president the Monroe Doctrine.

In the political tradition of the early 19th century, Adams as Secretary of State was considered the political heir to the presidency, but the old ways of choosing a president were giving way in 1824 before the clamor for a popular choice.

Within the one and only party (Democratic-Republican nicknamed “Republican”), sectionalism and factionalism were developing, and each section put up its own candidate for the presidency. Adams, the candidate of the North, fell behind Gen. Andrew Jackson in both popular and electoral votes but received more than William H. Crawford and Henry Clay. Since no candidate had a majority of electoral votes, the election was decided among the top three electoral vote winners by the House of Representatives in accordance with the 12th Amendment. Clay, who favored a program similar to that of Adams, threw his crucial support in the House to the New Englander.

Upon becoming President, Adams appointed Clay as Secretary of State. Jackson and his angry followers charged that a “corrupt bargain” had taken place and immediately began their campaign to wrest the presidency from Adams in 1828. (The Democratic-Republicans would drop the second half of their name prior to the 1828 presidential election. In addition, the Democrats would implement a nominating process so that they would have a single nominee going forward.)

Well aware that he would face hostility in Congress, Adams nevertheless proclaimed in his first Annual Message a spectacular national program. He proposed that the Federal Government bring the sections together with a network of highways and canals, and that it develop and conserve the public domain, using funds from the sale of public lands. In 1828, he broke ground for the 185-mile C & 0 Canal.

Adams also urged the United States to take a lead in the development of the arts and sciences through the establishment of a national university, the financing of scientific expeditions and the erection of an observatory. His critics declared such measures transcended constitutional limitations, and his fellow Democrats, mostly devotees of the party’s states’ rights, laissez-faire philosophy, promptly broke ranks with Adams. In response, other disenchanted Democrats, including some former Federalists, rallied behind Adams and founded the National Republican Party in 1825.

The campaign of 1828, in which his Jacksonian opponents charged him with corruption and public plunder, was an ordeal Adams did not easily bear. After his defeat at the hands of Jackson and the Democrats in what is generally recognized as one of the most contentious ever, Adams returned to his home state of Massachusetts, expecting to spend the remainder of his life enjoying his farm and his books.

Unexpectedly, in 1830, the Plymouth district elected him to the House of Representatives, and there for the remainder of his life he served as a powerful leader. Above all, he fought against circumscription of civil liberties.

Interestingly, Adams was the first president to serve in Congress after his term of office, and one of only two former presidents to do so (Andrew Johnson later served in the Senate). His tenure in the House of Representatives was prolific as Adams was elected to nine terms, serving for 17 years from 1831 until his death.(A man whose political affiliations included four political parties, Adams ran unsuccessfully for Governor of Massachusetts in 1833 on the Anti-Masonic ticket. His last ten years in the House were spent as a member of the newly formed Whig Party.)

In 1836, southern Congressmen passed a “gag rule” providing that the House automatically table petitions against slavery. Adams tirelessly fought the rule for eight years until finally he obtained its repeal.In 1841, Adams persuasivelyarguedon behalf of the Amistad captives’ in their petition for freedom before the Supreme Court in one of the most high-profile legal cases in US history.

In 1848, he collapsed on the floor of the House from a stroke and was carried to the Speaker’s Room, where two days later he died. He was buried (as were his father, mother and wife) at First Parish Church in Quincy. To the end, “Old Man Eloquent” had fought for what he considered right.