by Ken Moellman

Our founding fathers were not comfortable with the formation of political parties, but they also acknowledged that they were inevitable, and it was within the rights of people, as free men, to gather and assemble political parties. With few exceptions, there have been two primary parties in control, divided over one or two major issues.

Prior to the passage of the United States Constitution, the country was governed under the Articles of Confederation. Under the Articles, the states had most of the power, and the federal government’s job was to help coordinate efforts between states.

There were flaws with this system.

National defense was a major concern. States would send their state militias only when they wanted to, and there was a problem with pirates. Additionally, there was no unified trading system with foreign nations. Britain was engaging in “guerrilla” trading. They would starve states of trade, until a state was willing to undersell the next one. This led to serious problems within various states. So, the states called a constitutional convention to “revise” the Articles of Confederation and address these issues.

There were two primary factions in the debate to remedy the situation: Federalists and Anti-federalists. The federalists were in favor of replacing the Articles of Confederation. They were for strong national government. Most anti-federalists were in favor of amending the existing Articles of Confederation to address the primary issues. They were in favor of maintaining state power over the federal government.

These two factions waged a hard-fought battle, both behind closed doors, and in the media. At the end of the fight, however, the Federalists won. The Anti-federalists were able to create the Bill of Rights, as the initial ten amendments to the Constitution. (There were two other amendments proposed at that time, one was not ratified until May 7, 1992 as the 27th Amendment, and the other is technically still pending before the states).

Many on the Anti-federalist side, in the interest of national unity, eventually endorsed the final product: the United States Constitution.

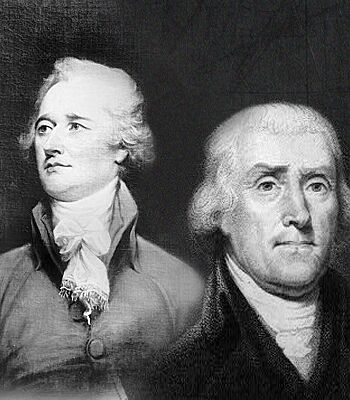

As the party system took hold, the Federalist Party became the home for the federalists under the initial leadership of Alexander Hamilton and later John Adams, while the Democratic-Republican Party became the home for the anti-federalists, after aligning behind Jefferson and Madison.

First Political Parties in America

The “First Party System” was the era of the first political parties: the aptly-named Federalist Party and the anti-federalist Democratic-Republican Party. Those in favor of stronger national government were originally termed “Federalists” by the news media of the day, eventually this group did form the Federalist Party, the party of Hamilton, Adams and Washington, although the latter never officially joined and often disagreed with Federalist views.

Many of the Tories (those who had opposed cessation from Britain from the start) joined the Federalist Party. Congregationalists and Episcopalians generally supported the Federalists, who supported the co-mingling of Church and State, and who sought to maintain close relations with Great Britain to enhance trade.

One of the most infamous acts from the Federalist Party came from the John Adams administration. The Alien and Sedition Acts, passed in 1798, imprisoned anyone who opposed the administration (run by the Federalists) as treasonous. The fight over the controversial acts led to a feud between party leaders Aaron Burr of the Democratic-Republicans and Federalist Alexander Hamilton, which was exacerbated after Hamilton helped sway the House of Representatives to choose Jefferson over Burr in the Presidential Election of 1800, leading to a duel between the men. Hamilton was killed in the duel and Burr became a fugitive. The public outrage over the event significantly weakened the Federalist Party. Nevertheless, the Federalists were able to control the judicial branch of government due to the appointments of Washington and Adams, and therefore empowered the federal judiciary to promote a Federalist agenda.

Federalist power peaked in 1798 as disenchantment over the Alien & Sedition acts mounted. The party’s death Nell, however, was its opposition to the War of 1812, which stemmed from its desire to maintain close relations with Great Britain to support trade. Following the end of the conflict in 1815, the Federalist Party suffered a swift decline. As the party faded away, its members joined other parties and the “Second Party System” began.

Formation and Split of the Democratic-Republicans

Around 1792, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison formed the Democratic-Republican Party from various factions of already-elected statesmen and a loose confederation of those opposed to the Federalists. The “Republicans,” as they were generally referred to, opposed a strong national government, favored France over Britain, expressed skepticism of the Federalist-dominated federal courts, and opposed a national Navy and a national bank.

Presbyterians, Baptists and other minority denominations tended to oppose co-mingling of Church and State, and therefore supported the Democratic-Republicans. In the media, this approach was used to smear the D-R’s as atheistic and belligerent towards religion.

The Democratic-Republicans (namely Jefferson and Madison) anonymously co-authored the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, as the Alien and Sedition Acts would have possibly seen them jailed, had they been attributed. These resolutions rejected strong national government and specifically spoke against the policies of the John Adams (Federalist) presidency.

The Democratic-Republicans were, in large part, an opposition party to the Federalist Party. They had formed in response to the formation of the Federalist Party, and of Federalist Party policies. As the Federalist Party collapsed, the Democratic-Republicans found themselves without a single target. Party unity began to fade. As the country continued to grow, the issues facing the country changed as well.

By the early 1820s, the philosophical lines between Democratic-Republican and Federalist became blurred. Jefferson and many “Old Republicans,” as they were called, still supported the platform of states’ rights but had reversed their policies on issues such as the controversy over the Bank of the United States (which had been chartered during the Madison administration in 1817). This caused a division within the Democratic-Republican Party.

Some would say that the Democratic-Republican Party died the day that Jefferson died; July 4th, 1826. Undoubtedly, the party had become divided over other issues, and, as the era of the “First Party System” came to a close, with the Federalist Party all but dead, the Democratic-Republicans divided into several factions, and new factions were forming behind new issues.

End of the “First Party System”

The “First Party System” came to a close in 1828, but the change began earlier. With the Federalist Party practically dead, Democratic-Republicans dominated politics. Nevertheless, divisions grew within the Democratic-Republicans.

The infighting came to a head in 1824, when the party had four separate candidates for President in the general election; all nominated in different ways. The four candidates were: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, William H. Crawford and Henry Clay. (John C. Calhoun had also been a candidate but opted to run for vice-president instead.)

The results for vice-president were clear: John C. Calhoun was the clear winner. However, there was no one with a straight majority of Presidential electoral votes; obtaining 131 of the 261 electoral votes was required for a victory. Jackson had the most electoral votes, with 99 electoral votes, followed by John Quincy Adams with 84, William H. Crawford with 41 and Henry Clay with 37.

Under the 12th Amendment, the top three Presidential candidates were then to be considered and voted upon by the House of Representatives. Jackson, Adams and Crawford were the top-three; Clay was excluded. Clay, however, was also the current Speaker of the House.

Jackson expected to become the next president, having won a plurality of the electoral and popular vote. However, as the election was now operating under the rules set forth under the 12th Amendment, each state only had one vote to cast for president.

Clay was not a fan of Jackson at all. In what is commonly criticized as the “corrupt bargain,” Clay threw his support behind Adams and coerced fellow Congressmen to vote for Adams. In return, Clay was made Adams’ Secretary of State, which at the time was generally the office from which the next president was elected.

The House voted and John Quincy Adams was the winner. The Jacksonian faction campaigned hard on this perceived corruption until the election of 1828, when the two men would square off again.

In the election of 1828, Jackson again challenged Adams, and there were no other major contenders. The Adams faction began to call themselves the “National Republicans.” The Jackson faction began to call themselves the “Democratic Party.” To complicate matters further, the siting vice-president of John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, became the vice-presidential running-mate of Andrew Jackson, the challenger to Adams’ presidency.

Jackson uprooted Adams in the election, but, more importantly, the split in the Democratic-Republican party caused the rise of the real “third” parties for the first time in American history.

The “Second Party” System

The implosion of the Democratic-Republican party, which resulted from the election of 1828, led to a new era in party politics. For the first time, the country saw the rise of more than two parties, some of which successfully obtained significant electoral results at the state and federal levels.

The Jacksonians, to be known as the Democratic Party, were the former Democratic-Republicans who aligned behind President Andrew Jackson. The National Republicans were former Democratic-Republicans who aligned behind John Quincy Adams, and against Andrew Jackson. The National Republican Party was absorbed in the 1830s by the Whig Party, which was founded in 1833.

The Anti-Masonic Party formed in New York in 1828 and was based upon the growing anti-Freemason sentiment in the country. Many feared that the Freemasons were a secret society of power brokers and elitists. In fact, some believed that the Freemasons sought to create a shadow government and murdered political opponents. The party lasted until approximately 1838 and was primarily absorbed into the Whig Party.

The Nullifier Party was formed in South Carolina in 1828 and was based upon state’s rights. The party supported the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions and the concept of state nullification of federal laws within the borders of a state. The movement behind the party was fueled by both high taxation and an economic recession, which hurt the southern states, especially South Carolina. The party lasted until the end of the 1830s, when it was absorbed into the Democratic Party.

The Whig Party formed in 1833 of former National Republicans, as well as members of the Anti-Masonic Party. The death of several leaders, including Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, in addition to a growing divide over the policy of slavery, led to the demise of the Whigs. The Whig Party officially remained a party until 1856 but was effectively finished with the birth of the Republican Party two years earlier. Whigs that did not join the Republican Party went to the Constitutional Union Party.

The Liberty Party was formed in New York and existed throughout the 1840s. The party singly focused on the issue of eliminating slavery and folded into the Free Soil Party in 1849.

The American Republican Party was a short-lived anti-immigration party that was founded in 1843 and changed its name to the Native American Party two years later. The remnants folded into the Know-Nothings in 1854, at the end of the “Second Party System.”

The Know-Nothings were a political movement formed in the 1840s, from members of the Whig Party and the Native American Party. It was not successful until the 1850s, when they merged with the American Republican Party and renamed themselves the American Party. They then elected representatives to the House and Senate. Primarily, they were an anti-Catholic and pro-temperance organization. The party was dissolved in 1860 at the beginning of the “Third Party System” and was mostly absorbed into the Republican Party.

The Free Soil Party was formed in the late 1840s, the second anti-slavery party during the Second Party System. The party was comprised of anti-slavery members of the Democratic Party, the Whig Party and the Liberty Party. This was a successful party, sending representatives to the House and Senate. They were a single-issue party that folded into the Republican Party shortly after its founding.

The Anti-Nebraska Party was an off-shoot of the Know-Nothings (American Party) formed in 1854. They held a deep moral opposition to slavery and were appalled by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The party existed for less than a year and quickly morphed into the Republican Party.

The Opposition Party formed in 1854 and was a short-lived party that attempted to provide a compromise on the growing divisions over slavery. The party was successful in electing 100 members to the House of Representatives but essentially ended in 1858. Members were encouraged to join the last member of the Whig Party in the Constitutional Union Party; however, some members joined the Conservative Party.

Each party had its own issues. Some parties were single-issue parties or single-issue splinters from other parties. Other parties were a caucus of several issues based around one or multiple principles. With the increased competition, innovations in the political landscape came as a result of the multiple parties during this time in our history, most notably the concept of the nominating convention.

Also significant was the greater extent of endorsement and cross-nomination of a single candidate by multiple parties, a practice also known as “fusion.” Fusion still exists in a select few instances today, such as in New York. During the Fourth Party System, fusion continued to play a role in party politics until it was eventually outlawed in most states at the turn of the 20th century

Officially ending in 1854, the second party system saw radical changes in policy and priorities in the country as the nation headed towards the bloodiest internal battle in its history.

Its like you read my mind! You appear to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do with a few pics to drive the message home a bit, but other than that, this is wonderful blog. A fantastic read. I’ll definitely be back.