by Harold Holzer

Perhaps the most surprising thing to modern Americans about the 1860 presidential campaign—the historic election that sent Abraham Lincoln to the White House—is how little actual campaigning the presidential candidates that year did. Of course, it was an era in which nominees for the nation’s rather remote highest office were expected to stay home and remain silent, allowing surrogates to engage in the rowdy business of politicking on their behalf. As recently as 1852, Mexican-American War hero Winfield Scott had broken precedent to take his incomparable military record and immense physical presence directly to the people. The appearances were not enough to prevent an embarrassing defeat, a fate the previous three generals to quest for the White House (Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor) had all avoided by letting their reputations speak for themselves.

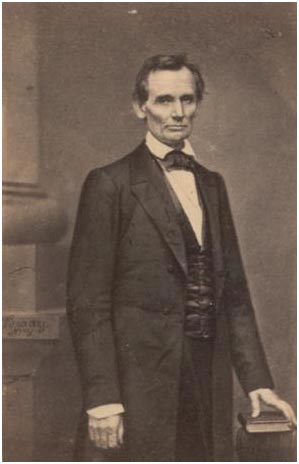

Abraham Lincoln had his photograph taken by Mathew Brady the day of the Cooper Union address in New York, February 27, 1860. (Gilder Lehrman Collection)

Abraham Lincoln may have had no military record to speak of—his experience in uniform had been relegated to a few “bloody struggles with the musquetoes [sic]”[1] during a rather tame Indian war nearly thirty years earlier—but he had a political record to spare, much of it already in print. Letting that record speak for him, Lincoln stayed resolutely close to his Springfield, Illinois, hometown during the contentious spring and summer of 1860. John Bell, nominee of the new Union Party, and John C. Breckinridge, choice of the Southern Democrats who broke from their party rather than nominate Stephen A. Douglas, did no personal campaigning either.

As the candidate of the Northern Democrats, Douglas, however, decided he had no choice but to take the Winfield Scott route. With nothing to lose—the party split already meant he could not automatically count on the bloc of Southern states that Democratic candidates routinely claimed on Election Day—Douglas headed toward New England on the wings of myriad unconvincing explanations involving family obligations. Those few who believed the excuses must have changed their minds when Douglas chose a circuitous itinerary that first took him south before heading east and north, permitting him to give campaign speeches whenever his train stopped to refuel. Neither the dodge nor the whistle-stopping worked.

In a certain way, the election of 1860 turned on a series of accidents and false assumptions. Most teachers and students already know the basic outlines of that historic campaign—but few understand how close it came to unraveling before Abraham Lincoln could claim final victory and take office.

One recently advanced theory is that Lincoln would have prevailed even without the split within the Democratic Party that year, an argument that has become increasingly popular in the age of quantitative history. Its proponents make an interesting point: after all, even if one of the candidates had dropped out, or if Douglas’s and Breckinridge’s votes had been added together, Lincoln still would have won in enough states to guarantee him an electoral majority. The problem here is the mistaken belief that a two- or even a three-way race would have produced the same political dynamic as the four-way contest of 1860. Loyalties can shift seismically in a political campaign depending on who enters, remains, or withdraws from election contests. In my view, the split didelect Lincoln after all. It not only divided the Democratic vote, it made that party’s cause more hopeless from the beginning. It is seldom mentioned, but Lincoln also won because Bell had no real organization behind him to drain as many votes from the Republicans as Breckinridge and Douglas did from each other.

At the time, one false assumption that altered the election—not to mention its aftermath—was the concern among Southern voters that Lincoln intended to act against slavery where it existed, palpably false on the record. Had there been no secession or rebellion, Lincoln was pledged only to prevent the spread of slavery into new western states—meaning that eventually, and only eventually, the pro-slavery majority in Congress would have diminished enough for Congress, not the President, to act against the peculiar institution. How long that might have taken is a matter of conjecture, but it is entirely likely that under this scenario slavery might have endured until the twentieth century. To Lincoln’s advantage, however, the South labored under an even more foolhardy assumption—believing that Douglas was as dangerous a threat to slavery as Lincoln. This was based on Douglas’s 1854 Popular Sovereignty initiative, which proposed to allow settlers in western territories not only to vote slavery in, but if they preferred, to vote it out. Douglas’s position was judged impure enough by the most conservative Democrats to split the party.

Then what was the complex 1860 election really about? First, it was a triumph of political organizing, with Republican Wide-Awakes and tireless Democrats taking to the streets on behalf of their candidates to light up the night throughout an autumn of torchlight parades, political demonstrations, and stump speeches by surrogates. Second, it was a successful effort by Republicans to overcome “fusion”—a last-minute campaign to unite Democrats around Breckinridge. The tactic was potent enough so that more Pennsylvanians ended up voting for the Southern than the Northern candidate—perhaps a mark of respect for native son James Buchanan, the outgoing chief executive under whom Breckinridge had served as vice president. Buchanan loathed Douglas, and seemed delighted to sabotage what was left of his campaign. Had the fusion effort started earlier, or succeeded as well in other Northern areas as it did in President Buchanan’s home territory, Lincoln might have faced a real threat. Democrats hoped to deny Lincoln enough electoral votes in swing states to throw the election to the House of Representatives, where their party held such a large majority that the next president would almost certainly be a Democrat. Douglas believed it his best chance, and it was a very real chance in the fall of 1860.

Meanwhile, to the extent Republicans could control the 1860 message, the campaign avoided discussions about slavery and instead focused primarily on their nominee’s personal story: his inspiring rise from log cabin to the threshold of the White House. This remained Lincoln’s strongest weapon in the long campaign.

What few counted on—probably not even the Republican candidate—was Lincoln’s enormous appeal. Modest, even self-deprecatory about his physical appearance, Lincoln nonetheless wisely made himself available to photographers, painters, and even sculptors, to record images that could be mass-produced and widely distributed in the form of tokens, banners, keepsakes, mailing envelopes, and popular prints for the family parlor. All but unknown outside Illinois when he won the party nomination in May 1860, Lincoln might have remained a remote (and less successful) national candidate had he not actively conspired in the promulgation of his own image. Photographers like Mathew Brady and Alexander Hesler and artists like Thomas Hicks and John Henry Brown, among others, not only brought his face before the public, but made that face look much better than the original. That Lincoln understood the impact of such images cannot be doubted. He took the time and trouble to pose for Brady in New York on the busy, nerve-wracking day of his Cooper Union address on February 27, 1860. The result inspired more campaign prints that year than any other. Lincoln jocularly referred to the portrait as “my shaddow”[2] but the shadow it cast loomed large. Lincoln himself later said, “Brady and the Cooper Institute speech made me president.”[3]

He was right on both counts. Though he had made the New York speech nearly three months before his nomination, the Cooper Union address figured mightily in the election, as did the Lincoln-Douglas Senate debates two years earlier, particularly since Lincoln decided to say nothing new after saying so much at these seminal events. No less astute than modern politicians who conveniently time autobiographies to the launching of their campaigns, Lincoln personally arranged the publication of the debates in time for the Republican convention, and encouraged the reappearance of a fancy, footnoted pamphlet version of Cooper Union in time for the campaign. Thereafter, visitors and correspondents seeking Lincoln’s views on current issues were directed to these publications. The Lincoln-Douglas reprint became a best seller.

After October state elections demonstrated reassuring strength among the Republicans, Lincoln and his supporters grew somewhat more confident. But they still feared that fusion might throw the decision to the House of Representatives, where they stood no chance of success. Fortunately for Republicans, the Democrats ultimately hated each other more than they hated Lincoln. Lincoln ended up with less than 40 percent of the popular vote, but won a comfortable majority in the Electoral College by amassing 180 votes to just 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell, and an appalling 12 (from Missouri and New Jersey) for Douglas. Had Lincoln said more, Republicans voted less (turnout was estimated at 80 percent), fusion succeeded better, or Bell organized more successfully, the result might have been different. As it was, Lincoln’s triumph proved the most sectional victory in American political history, a factor soon cited by Americans from the Deep South determined to use it as an excuse to leave the Union. In all respects—for how it was conducted, and for what it produced—it was not only the most important election of the century, but arguably the most distinctive.

It is worth noting that, for some, including Lincoln himself, the election was not completely decided on November 6, 1860. Popular votes were indeed cast and allied that day, but electors were not scheduled to meet and cast their own, more important votes until December. Lincoln and his inner circle worried that Democratic electors might yet unify around a single candidate—or worse, that Republicans, worried about secession, might themselves look for alternatives to Lincoln! In fact, several New York Republicans did suggest dumping Lincoln in order to save the Union. Meanwhile, no one in the North was absolutely certain that Southern electors would bother to meet, especially in states like South Carolina, Mississippi, and Georgia, which had already taken steps to organize secession conventions. If these states did not participate in the traditional process, could the Electoral College proceed? What would constitute a quorum? No one, least of all Lincoln, knew the answers to these vexing questions.

As it turned out, the electors met in their respective state capitals as scheduled and proceeded to send their sealed ballots to Washington (some have argued that by this time the Deep South states were in fact eager to see Lincoln elected in order to fuel public sympathy for disunion). But even then, with John Breckinridge later scheduled to open and read these tallies—acting in his role as president of the Senate—it remained possible that something might yet happen to sabotage or scuttle the official ceremony. And then what? In the end, it took old Winfield Scott, the defeated Whig candidate for president in 1852, to guarantee the formal election of Abraham Lincoln. The general-in-chief ordered heavy-gauge artillery to Capitol Hill before the February meeting and warned that “any man who attempted by force or unparliamentary disorder to obstruct or interfere with the lawful count” would be “lashed to the muzzle of a twelve-pounder and fired out of a window of the Capitol.”[4]

Lincoln did not officially win the presidency until February 15, 1861. He received the news in Columbus, Ohio, in the midst of a pre-inaugural tour as boisterously public as his personal presidential campaign had been restrained and mute. Until that moment, he may have won an election, but he still was not absolutely sure he could organize an administration. By the numbers, the election did not seem close; but it was achingly so, and remained in a way unresolved and undecided until three weeks before the swearing-in.

By the way, Abraham Lincoln never voted for himself—he snipped his name from the ballot he cast in Springfield on November 6. But just enough of his contemporaries did to make him president.

________________________________________

[1] Speech in the House of Representatives, July 27, 1848, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8 vols. (New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953–1955), 1:510.

[2] Lincoln to Harvey G. Eastman, April 7, 1860, Collected Works, 4:39–40.

[3] George Alfred Townsend, “Still Taking Pictures,” New York World, April 12, 1891.

[4] Quoted in L. E. Chittenden, Recollections of President Lincoln and His Administration (New York: Harper & Bros., 1891), 38.

________________________________________

Harold Holzer is the author, co-author, and editor of more than forty books on Abraham Lincoln, including most recently, Emancipating Lincoln: The Emancipation Proclamation in Text, Context, and Memory (2012); Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860–1861 (2008); and Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President (2004). He is a Hertog Fellow at the New-York Historical Society, Senior Vice President for External Affairs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Chairman of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation.