by: Glenn R. Swift

Gently nestled just a few miles inland from Southern California’s Gold Coast lays the tranquil community of San Juan Capistrano. Made famous by Leon Rene’s 1939 hit, “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano,” this exquisite, pedestrian-friendly town offers a unique glimpse into California’s colorful and distant past.

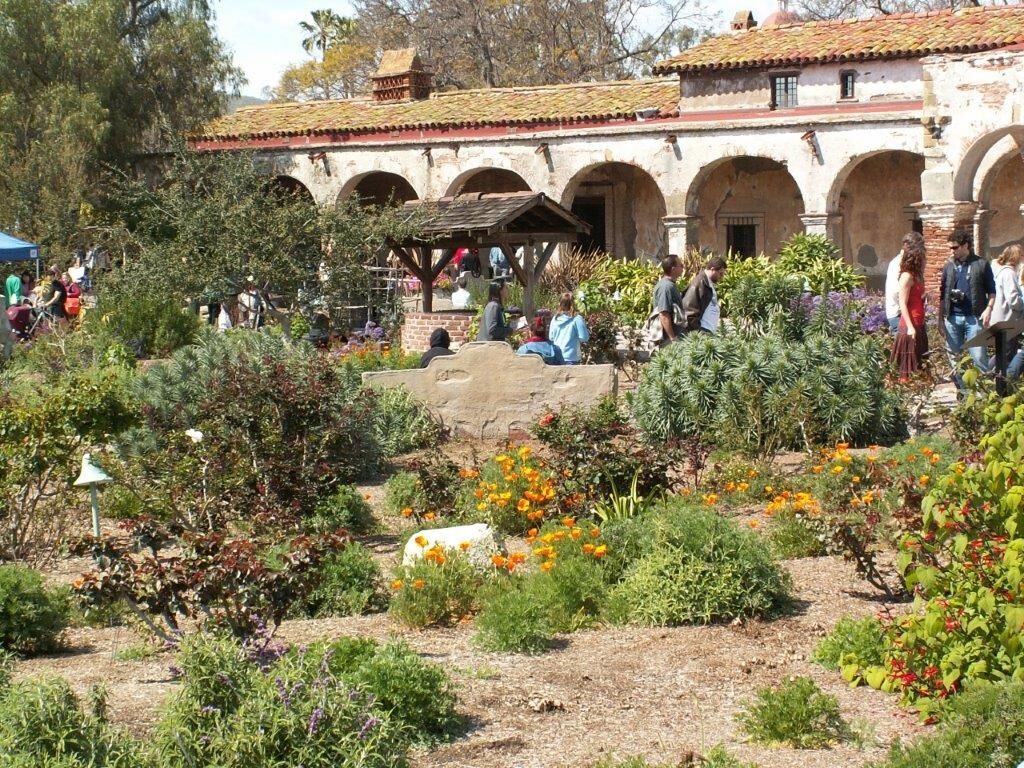

Known for generations by the faithful as the “Jewel of the Missions,” San Juan Capistrano was founded November 1, 1776 by Father Junipero Serra. An elaborate establishment, complete with numerous workshops, loom rooms, tallow vats and a massive stone church, San Juan Capistrano was the largest and most important of the twenty-one Spanish missions established by Franciscan friars along California’s El Camino Real (“Royal Highway”) in the 18th century.

Like all the missions, San Juan Capistrano was an essential part of the Spanish colonial structure in California. Because the region was so sparsely settled, the Spanish government was anxious to prevent rival colonial powers from claiming the territory. With this in mind, a chain of missions was established near the coast and about a day’s ride from each other. Spiritual ambitions aside, the primary function of the missions was to Christianize, pacify and educate the indigenous peoples so that they would become loyal Spanish subjects. The mission also supported the orderly development of the local pueblo (“village”).

Parish records just after the turn of the early nineteenth century reveal that over 31,000 animals (cattle, sheep, horses, mules, goats and pigs) were owned and cared for by the Mission. In addition, there were over 1300 Indians under the care of the padres. In this regard, San Juan Capistrano was very successful. However, the Mission’s Golden Age was short lived.

A massive earthquake in 1812 destroyed the Great Stone Church and severely damaged a number of other structures. The earthquake proved to be a harbinger of what was to come. Two decades later Mexico gained independence from Spain, but the new nation could not afford to support the California missions. So, in 1834, the Mexican government decided to secularize the missions and sell the land. The Indians were offered the lands first, but they either did not want them or could not afford to buy them.

Eventually, the land was divided up and sold. A few missions remained in the hands of the Spanish Catholic fathers, but many others were used for all kinds of other purposes. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln returned all the mission lands to the Catholic church, but by this time many of the California missions were in ruins.

In the twentieth century, many of the neglected California Spanish missions were restored or rebuilt. Most of them (as is the mission in San Juan Capistrano) are still active parish churches today, and they have excellent museums and beautiful, interesting ruins.

As for our feathered friends, the swallows return to Capistrano on March 19th, St. Joseph’s Day. They come from the Holy Land, says the legend, carrying a twig in their beaks, which they drop on the ocean when they want to rest during their journey. As romantic as the legend sounds, it isn’t true. Ornithologists have tracked the birds to Argentina where they spend the winter, returning in the spring to raise their young.

The Capistrano birds are cliff swallows, which have probably been returning to the area for centuries. They transferred their nests to the eaves of the Mission when it was built because of its convenient location near two rivers, which they needed for mud. Swallows build their nests out of tiny granules of mud piled on top of one another to form an inverted pouch with a funnel-like opening. They return to the same nests each year, and, if the nests haven’t survived the winter, they often rebuild in the same place.

As San Juan Capistrano has grown, the swallows have found more eaves to nest under, yet their food supply has dwindled. Insects necessary to their survival thrive in open fields, particularly those near riverbeds. The reduction in numbers of the insects (due to the development of the area) has caused the swallows to locate further from the center of town, which explains why visitors no longer see clouds of swallows descending on the Mission, as they once did.

Swallows are still the town’s most famous citizens, well-known and well-loved, protected in San Juan Capistrano by ordinance, which declares the city a bird sanctuary. Romantics all over the world consider the swallows one of the best remains of the colorful past of early California.