by Rosie Tanabe

The Seneca Falls Convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York on July 19 and 20, 1848, was the first women’s rights convention held in the United States, and as a result it’s often called the birthplace of feminism. Prominent at the 1848 convention were leading reformers, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott.

Different groups at different times have turned to the founding documents of the United States to meet their needs and to declare their entitlement to the promises of the American Revolution. At Seneca Falls on those two summer days of 1848, a group of American women and men met to discuss the legal limitations imposed on women during this period. Their consciousness of those limitations had been raised by their participation in the anti-slavery movement; eventually they used the language and structure of the United States Declaration of Independence to state their claim to the rights they felt women were entitled to as American citizens in the Declaration of Sentiments.

Seneca Falls was in a key location at the time, on the Great Western Highway, which ran west from Albany, New York, gave travelers access to the West. The village’s water power spurred the development of manufacturing industries, most notably various mills and pump manufacturers. The village also was part of New York’s canal system, as the Seneca River through the village had been turned into canals and connected to the Erie Canal.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony

Lucretia Mott

Background

In the 1840s, the United States was in the throes of cultural and economic change. In the years since the American Revolution and Constitutional Convention, the nation’s geographic boundaries and population had more than doubled; the population had shifted significantly westward, and many Americans’ daily lives had drifted away from Thomas Jefferson’s vision of a nation composed of independent farmers. Instead, farmers, artisans and manufacturers existed in a world built around cash crops, manufactured goods, banks and distant markets. Historians generally refer to this shift from production for a local economy based on a series of shared relationships to production for a distant, unknown market as the Market Revolution.

Not all Americans welcomed these changes, which often left them feeling isolated and cut them off from traditional sources of community and comfort. In an effort to regain a sense of community and control over their nation’s future, Americans, especially women, formed and joined reform societies. They were inspired by the message of the Second Great Awakening (a religious movement that emphasized human potential and forgiveness of sin) and the Transcendentalist message of humanity’s innate goodness; reformers joined together in organizations aimed at improving life in the country. These groups attacked what they perceived as the various wrongs in their society, including the lack of free public school education for both boys and girls, the inhumane treatment of mentally ill patients and criminals, the evil of slavery, the widespread use of alcohol, and the “rights and wrongs” of American women’s legal position. The Seneca Falls Convention is a part of this larger period of social reform movements, a time when concern about the rights of various groups percolated to the surface.

Many factors contributed to bringing about the 1848 convention. Women of the Revolutionary era, such as Abigail Adams and Judith Sargent Murray, raised questions about what the Declaration of Independence would mean to them, but there had never been a large scale public meeting to discuss this topic until Seneca Falls. According to America’s History, after the American Revolution, many new social roles for women emerged. With the men preoccupied with the war effort, it was up to women to take over many of their responsibilities on the home-front.

As a result, women were able to establish a place for themselves in society. Women such as Catharine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe began writing about women’s moral superiority and publishing their works. Many women began participating in reform organizations whose goals were to improve the lives of others and to fight for the rights of those who could not speak for themselves, such as schoolchildren and the mentally ill. In 1834, the New York Female Reform Society was established with Lydia Finney as its president. It attempted to provide a moral working atmosphere to keep women out of prostitution. Other female leaders, such as Dorothea Dix, focused their energies on prison reform in the 1830s.

It was during this time that women’s role as educators also emerged. Catharine Beecher established several academies for women, and her writings suggested that women were the most appropriate candidates for teaching positions. Finally, the abolitionist movement gave women another opportunity to become involved outside of the domestic sphere. With all of these structural changes, the time was ripe for a close examination of women’s rights as well. A consciousness-raising experience, however, was necessary to turn these women’s thoughts to their own condition.

The triggering incident was a direct result of participation in anti-slavery organizations by Stanton and Mott. Anti-slavery societies proliferated in the Northeast region of the US and in some parts of what today we call the Midwest. Many of these organizations had female members. According to Cristine Stansell in The Road from Seneca Falls, the abolitionist movement was what allowed women to get their foot in the door. They then began to use their involvement to promote women’s rights. This caused the movement to split into two groups, the radicals and the conservatives. The radicals promoted equality for all, including women, while the conservatives clung to traditional gender roles. It was these conservatives who attempted to constrain women to the domestic sphere by refusing to let them participate in the abolitionist cause.

In 1840, the World Anti-Slavery Convention met in London; some of the American groups elected women as their representatives to this meeting. Once in London, after a lengthy debate, the female representatives were denied their rightful seats and consigned to the balcony by conservative abolitionists. Stanton and Mott met at this meeting while sitting on the balcony and walking through the streets of London. Eight years later, the two pioneers called a convention to discuss women’s rights.

The Call for Women’s Rights (1848)

On July 14, 1848, the Seneca County Courier announced that on the following Wednesday and Thursday (the 19th and 20th) a “convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women” would be held. The Convention had been planned at a meeting a few days earlier in nearby Waterloo, NY, attended by Lucretia Mott of Philadelphia, Elizabeth Cady Stanton of Seneca Falls, Jane Hunt of Waterloo and Elizabeth McClintock of Waterloo. The meeting took place at the home of Jane Hunt.

The Convention would take place in the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls. While the first session was planned to be exclusively for women, the men who arrived for the event were not turned away. On the second day, the Convention approved a document titled the Declaration of Sentiments, a statement written by Stanton and others and modeled on the Declaration of Independence.

In adapting the Declaration of Independence, Stanton and her co-authors replaced “King George” with “all men” as the agent of women’s oppressed condition and compiled a suitable list of grievances, just as the colonists did in the Declaration of Independence. These grievances reflected the severe limitations on women’s legal rights in America at this time: women could not vote; they could not participate in the creation of laws that they had to obey; their property was taxed. Further, in the relatively unusual case of a divorce, custody of children was virtually automatically awarded to the father; access to the professions and higher education generally was closed to women, and most churches barred women from participating publicly in the ministry or other positions of authority.

The Declaration of Sentiments proclaimed that “all men and women were created equal” and that the undersigned would employ all methods at their disposal to right these wrongs. The document was discussed in length by those in attendance. It was the voting provision which caused the most debate, but ultimately the document was adopted and signed with hardly any alterations and was published as a pamphlet. Of the approximately 300 people who attended the Convention, 100 signed the Declaration of Sentiments.

David Walker, in his efforts to gain recognition of the legal rights of black Americans, similarly used the Declaration of Independence in his call to the American people on behalf of the oppressed black population, both freed and enslaved. In the 1840s and even today, the language of Thomas Jefferson resonates through American life. Many Americans believe that the ideals of the Revolution are applicable to life in the present, just as the women of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention felt those ideals spoke to them.

Historian Gerda Lerner has pointed out that, in addition to ideas of social contract and natural rights, religious ideas provided a second fundamental source for the Declaration of Sentiments. Most of the women attending the convention had been active in Quaker or evangelical Methodist movements. The document therefore draws from writings by the evangelical Quaker Sarah Grimke to make biblical claims that God had created women equal and that man had usurped this authority by establishing “absolute tyranny” over woman. According to Jami Carlacio, Grimke’s writings opened the public’s eyes to ideas like women’s rights, and, for the first time, they were willing to question convention.

Convention Caricature

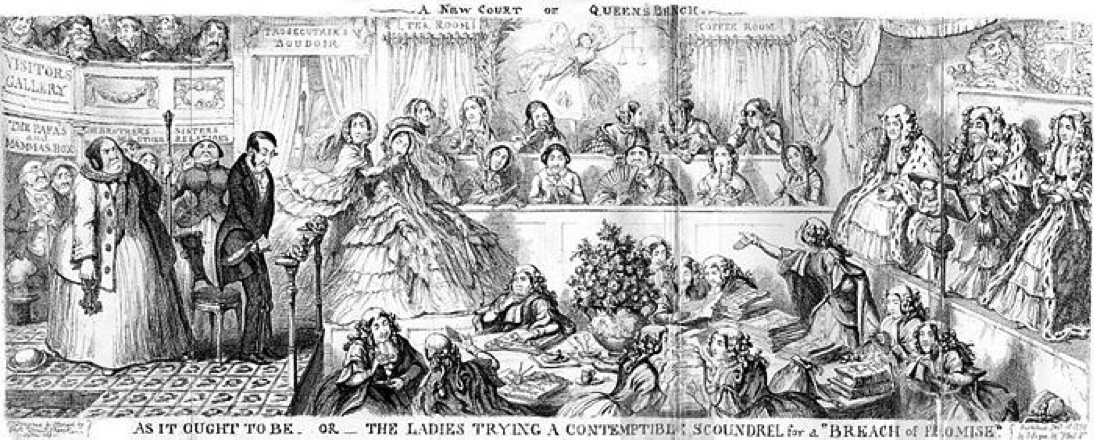

A New Court of Queen’s Bench, As it Ought to Be—Or—The Ladies Trying a Contemptible Scoundrel for a “Breach of Promise,” an 1849 caricature by George Cruikshank for the 1850 Comic Almanack.

This is an elaborate satire on what the imagined results of women’s rights efforts would be, mocking the idea of women ever becoming lawyers, judges and legal officers. (The early feminist movement had begun to attract public attention after the Seneca Falls convention of 1848.) Much of the humor (which may not be entirely obvious to twenty-first century eyes) was intended to arise from the way in which the rather grim and austere all-male world of the mid-nineteenth century English law receives various touches of feminine domesticity, giving rise to juxtapositions that would have seemed ludicrously incongruous and inherently absurd to many at the time.

The auxiliary spaces around the main area of the courtroom are “The Papas and Mammas Box,” “The Brothers, Sisters, and Other Relations,” “Visitors Gallery,” “Prosecutrix’s Boudoir,” “Tea Room,” and “Coffee Room.”

At the left, the female warder guards the prisoner/defendant, while the female bailiff holds a staff. The accuser sits next to the jury, supported by a relative who casts a reproachful glare at the defendant. The lawyers etc. sit at the table; at the right, the main “prosecutrix” declaims to the jury, with piles of paper labeled “Introductory Correspondence &c. &c. &c.,” “Declaration & Proposal &c. &c. &c.,” and “The Breaking off” in front of her. The other lawyers (going clockwise) are looking at: a mirror propped up against “The Book of Beauty,” an advertisement for “Don Giovanni” at Her Majesty’s Theatre, “Boz’s Law Reports: In Cause of Bardell v. Pickwick” (a reference to an incident in Dickens’ Pickwick Papers), and La Belle Assemblée (a fashion magazine).

Incongruous feminine touches include the ribbons and bows in the legal wigs of the lawyers and judges, the huge floral centerpiece on the lawyers’ table, and the judges, lawyers and jurywomen who are knitting, embroidering, smelling nosegays, plying fans and eating sweets.

The blindfolded symbolic representation of Justice at the center top is dressed as a ballerina, while the lion that serves as a supporter to the royal arms at upper right has the hairstyle and mustache of a parlor dandy and ladies’ man of the period, and the middle judge’s book rests on a blindfolded cupid—these last two suggesting that the judges’ decisions will be influenced by the handsomeness of males who appear before the court.

All the males—other than the defendant, and the father and brother of the plaintiff—are squeezed into the visitors’ gallery at upper left. Of course, Cruikshank doesn’t seem to find it remarkable that under the normal course of the British law in 1849, women defendants would face all male judges, jury and lawyers, working within a law passed by all male MPs.